How did the 'Star' come to win the first ever ECF 'Rally of the Year' award?

In early June the club's E&S Rally committee invited me to join them. Two stalwarts were highly experienced guys: Chief Marshall Arthur Fletcher was quite used to getting hundreds of willing helpers out to Wales; and Clerk of the Course Harry Morgan. Harry, in his 60s and a one-time Triumph works driver, was a gentle, lovable, bighearted, quietly-spoken Welshman. He had been hurt by ST's stick after the 61 event. Harry offered me 100% free rein to do whatever was needed, for every aspect of the rally's organisation, to make the 62 event a modern, up-to-date success. They sure gambled with a 23-year-old 'rookie'!

During the next nine months I set about the task with the maniacal energy only raving mad 23/24-year-olds can muster. (Read Brown again!) I worked prodigiously on what follows.

At its simplest the 'Star' would have none of the stupidities and amateur touches I had encountered on the handful of top events I had competed in from January to May 1961. (Later, in September, the London was just as bad.)

As a first step I made some money for the rally from commercialising the 'regs'. I got on the phone and sold advertising to numerous national companies, including the likes of National Benzole. Getting on for £500 was raised; that's about £8,000 today lads! The 180 entrants, the maximum allowed, had the chance to chase the best-e©ver cash prizes offered by any national. They equalled, if not bettered, the 'cash' prizes available on the 1962 RAC!

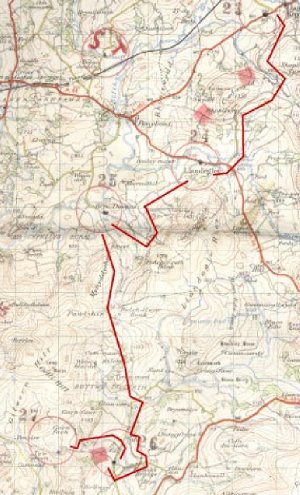

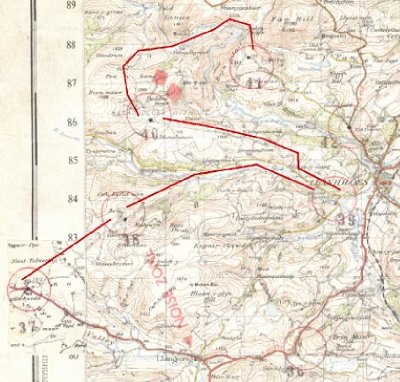

I chose 128 as the 'marked map'. After months of detailed research on the ground I finalised the route. Scrutineering, etc., took place at Fulwoods in Wolverhampton; then followed an easy run west to three miles north-west of Bishop's Castle. One novelty was the printing and affixing of two patches on both the eastern edge of 128 (a reprint of part of 129 ensured, from the 'real' start control 'X' on the B4385, a three-control 'taster' of the myriad goodies to come); and also the western edge (allowing me to make full use of the tough pays between the A44 and B4518, east of Hafren Forest, and including lanes which are now covered by the very deep waters of Llyn Clywedog).

I decided on 51 controls for the total 'competitive' distance of what I would guess now was about 160 miles. Many parts of the route had 'gaggles' of four to five controls with tight timing of this sort: 2.4m (4 mins); 2.3m (4 mins); 2.8m (5 mins); 2.3m (4 mins); a total of 9.8m in 17 minutes. Constant climbs and descents played a major part, one quickly following the other. Absurd pruning was not employed; but the pressure on time was ratcheted-up relentlessly from control to control in each of the numerous gaggles.

One must was my decision to ensure every gate was left open (most were manned to ensure they remained so and that livestock didn't wander). I and others visited some 50 or more farms to ensure farmers knew when and where the 180 competitors were driving. One benefit of this openness was that hundreds upon hundreds of 'locals' were spectators on the night of the rally.

Another must meant no daylight dicing for any of the 180 entrants. First finishers would arrive at Control 52, the Metropole in Llandrindod Wells, not long after 5.00 a.m. on Sunday for an early breakfast (the tough part had finished at control 51, 30 minutes earlier). Even starter 180 was not going to be dicing in daylight. The rally 'proper' started at 11.01 p.m. on Saturday.

A third must meant that there would be no local knowledge of any kind. I marked 15 'non-goers' with a red-ink diamond on each map; so the correct route was entirely obvious at all times. 'Out of Bounds' areas and no 'Noise zones' were also marked on each map - and marshalled on the night. In addition, again on the night, a considerable number of fluorescent arrows were placed at all 'tricky' junctions or turns; these ensured that mayhem was avoided by cars turning around in off-route farmyards or other private driveways, etc. The end result would be a rally won by the finest combination of car, driver and navigator - with all three on song!

The onerous task of marking-up the 180 competitors' maps was done by yours truly. This ensured all the scores of markings on each map were 100% accurate. I checked and re-checked them many times. The same went for all the maps and other details given to the sector and control marshals. Of the latter we reckoned getting-on for about 400-500 were out that night, officiating in varying capacities. Most control sites had braziers, lights and other camping aids; probably four to five cars were in place at each control; all off the road and some out of sight.

Perhaps the most innovative and practical benefit on the night was Doctor Peter 'Young' Carlyle's ('PY' to his pals) new 'timing' system. This worked on the basis of 180 pocket watches (you took your own on the Morecambe), properly calibrated and sealed in glass-topped boxes, supplied by the enthusiastic and engaging Cannock jeweller, Frank Duschenes. He set back all the clocks from G.M.T. by the number of minutes represented by the competitors' rally numbers.

So, at the start of the rally proper (11.01 p.m.), just east of 128, car number one was set-off by a marshal at 11.00 p.m. on the entrant's watch; this, in turn, was the same for all 180 entrants. Let's say by control five that the on-time arrival was 11.20. The marshals at control five had a set of 200 A5-sized cards, all with the control number and 30 printed boxes showing 11.20 and '0' in box one; 11.21 and '1' in the second box; and so on up to 30. (Over 30 meant out of time; and no card.). A rally car arrived at the control; the watch box (all with identical faces) was held by the navigator at the car window; the time was shouted out by a marshal with a suitable lamp; another put an 'X' in the time-of-arrival box; the card was handed to the navigator. Another marshal kept an audit trail of each car's rally number and time of arrival (in case of later disputes). On the long final run-in to breakfast the navigator inscribed his car rally number on each of the 52 control cards.

As a result of this new and novel system cars were getting through controls in three to five seconds!

Back to the 'gaggles' of controls. I knew that two, in particular, would sort out the real men from the boys; in reality that meant sorting out Pat Moss from both the men and the boys!

One was a sequence of controls (23-27) south from the A488 north-east of Llandrindod Wells, across the A44 at Llandegley, over Bwlch-llwyn Bank, south to Frank's Bridge, past 'Cwm' in 1056, to control 27 on the 976 spot-height at MR 100563.

Only two drivers cleaned this 'gaggle': Pat Moss and Alec Griffiths. Another very tough 'gaggle' (37-41) was in the pays mentioned earlier: starting off the western edge of 128 (A44), the lanes climbed up and over from the Wye to the Severn, then up and over from the Severn to the Afon Clywedog, and then a sharp climb south to control 41 at MR 922877 (a mile or so of this last section is now at the bottom of the very deep Llyn Clywedog, a man-made reservoir). Only three cleared this: Pat Moss, Tony Fisher and Brian Harper.

(A third gaggle, controls 33-35, north-east of St-Harmon (9872), proved tricky; only eight were clean. As did controls 47-51, south-west of Newtown; only 11 lost no time.)

At Llandrindod Wells the results were the fastest ever produced for 180 cars (172 started) visiting 52 controls. A wide-awake team (all rising from hotel beds at 5.00 a.m.), working in twos and under 'PY's' supervision, marked-up each competitor's 52 cards on to long printed strips. For each control all that was needed were the figures on the cards representing 'minutes late' at each control. If an example read '0', '0', '1', '1', '0', '1' for the first six controls, that meant two minutes had been lost by control six. Results for each competitor were available just minutes after they handed in their set of cards. Overall results were announced within 15 minutes of the last car arriving at the Metropole. Awards were presented at 9.00 a.m.

The night of March 17/18 1962 was clear and mild - with no frost, snow or fog. The rally was a resounding success. The winners, Pat Moss and David Stone, cleaned the route. David Seigle-Morris and John Brown were second (three minutes lost). Tony Fisher and Brian Melia were third (four minutes lost). The next lost five minutes, the next six, three lost seven, and the next five lost 8, 11, 12, 13 and 14 minutes. Staggered perfection!

Every control had been cleaned by at least two competitors; 70 cars, from 172 starters, visited all 52 controls within the 30 minutes deadline. The winning driver, Pat Moss, demonstrated with a ruthless vengeance just why she was the fastest Brit at that time. David Stone, too, didn't miss a thing on the night. The duo, both masters of their respective crafts, together with their fabulous Saab, produced a veritable tour de force.

The overall standard of club rally organisation was racheted-up by several 'clicks' that March night. Slipshod organisation began, slowly but surely, to disappear over later years. New higher standards had been set; and have since been improved even further. Despite the 'success' I've had with my books and articles, and all the plaudits from critics and readers (some ear-thumping, too, my friends),I still feel a strong sense of quiet satisfaction in ensuring all went well with the so-memorable 62 Star, a rally which restored 'common sense' to rallying. Hundreds of willing folk put in a massive amount of work to achieve that basic objective. I treasure to this day a letter I received from Pat Moss at White Cloud Farm, saying simply: 'I certainly did enjoy the Rally very much - it was the best I have done for a very long time.' My only regret: that ST wasn't able to do the event - and make Harry Morgan a happy man. Rallying, for entrants and helpers, was fun in those days.

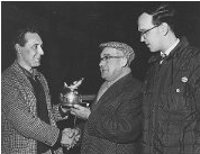

At the end of 1962 W.W.S.S.C.C. won the first-ever ECF 'Rally of the Year' by a landslide - voted for by ECF members who took part in the season's many Championship events. The club's reward, held for one year (and again in later years), was the now-famous, but then brand new, leaping silver fish. By 1964 Richard Harper took over the Star baton; and Colin Francis continued the good work later in the 60s. The name of the prestigious national has changed many times since its start in 1958, as has the character of the event.